"I’m smart. I faced that a long time ago," Tommy Webb exclaimed with a mischievous look. "I have an excellent memory. God provided me with that. Nothing I could do about it one way or the other. I’m old enough now I look at it realistically, and I was smart to start with. It was a big help," he laughed.

Thomas Gray Webb was born in Smithville in 1931 to Thomas Benton (T.B.) Webb, a school teacher who later served at the state department of education, and Gladys Gray Webb.

"I was born at home on South Mountain Street," he told the Review. "My grandmother and my mother’s aunt were there, and Dr. Cotton from Alexandria. There was no resident doctor in Smithville at the time.

"My mother was left an orphan when she was 12," he continued. "She came from Woodbury to live with her mother’s sister Ruby and her husband Jim Bell, who was a dentist. His office was on the square, above where Jeremy Trapp’s office is now. I still have the spittoon from his office.

"We thought the corner at Webb’s Drug store was heaven," he said. "It was the place to be. They had tables in the window, and you could sit there and see everybody."

Webb attended school in DeKalb County, and he said he was always glad to help his fellow students.

"If somebody wanted to copy off my paper, I let them," Webb said. "I just wanted to help out. We had a lot of true-false tests, and the teachers didn’t have any way to run off copies, so the test would be on the blackboard. I was in freshman algebra.

"I was a little, scrawny thing. Christine Lawrence sat right behind me, and she was a big girl. She said ‘Listen, this is the third year I’ve taken this class, and I’ve got to pass this time or I won’t graduate. When we have a test, you scoot over so I can see your paper.’ She wasn’t mean about it. She was nice, and I was too, so I did. Years later I went to see her in the nursing home. She said ‘Remember when I copied off your paper? I never would have got through without you.’ I told her I was just glad I could help, and I was."

Webb became emotional when recalling the death of his best friend in high school.

"The old high school auditorium seated 600 people," he said. "Logan Love was my best friend. We’d been best friends for about two years. I worked with him on the farm, and spent the night there almost every Saturday.

"He told me one day that when he got out of school he was leaving here, that only a couple of people cared anything about him, and that he was going to leave. He died at 17 in a car wreck. They had his funeral in that auditorium, and it was full. 600 people. And he thought nobody cared anything about him. I still think about him."

He went to Peabody College after graduating from high school.

"I had to come home every weekend, and that interfered with a biology lab I had," he shared. "I missed it nine weeks in a row, and I got a C-plus. I ended up taking an algebra class because it was early, and I could still catch the bus to Smithville on the weekend. I got certified in math. I hated math, but I got certified to teach it.

"I had to get back to Smithville every weekend because Saturday in Smithville was wonderful at that time," Webb said. "Three or four years later everybody got a TV, and it sort of dried up, but before that everybody came to town on Saturday. It was like a big reunion every weekend. I had to be here for it. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. I wouldn’t have missed it for that biology lab, that’s for sure.

"I never took notes in college," he went on. "I could remember what the instructor said. I finished college in three years, and started teaching. I was 21 on the 30th of July, and I started teaching the next week at Mahathy Hill, which was out near Banks Church. The building is still standing. I boarded with Elmer and Flora Warren, and hitchhiked home for the weekend.

"We had a good school. I taught the upper grades, Ms. Elizabeth Cantrell, who had been teaching 30 years, had the lower grades. She said she wanted me to be the principal. We had a lunch program, and we had to have certain things for that. Cabbage met the requirements for citrus, and we had cabbage every day. We had about 45 children between the two rooms.

"We had the Shehanes: Frank, Francis, May and Mary. Zeb Caldwell was a student, but he was nearly as old as I was. I went home with him once and we went coon hunting with his father. We rode the school bus to his house.

"His father, Will, had a miner’s lamp. Zeb was following him, and could see a little. I was following Zeb, and I was just wandering around in the dark. We hunted until two a.m., and got up, and got back on the school bus at six. We got a coon, though. Zeb’s still my friend now.

"Out there they didn’t have TV, so we’d go visit the neighbors. I got acquainted with everybody out there. I never liked TV. We had one at home, but by then I was already out with my friends having fun, and I never watched it. Still don’t, and I’ve never had a phone.

"I was at Mahathy Hill until about six weeks before the end of the school year, and then they took me away to the army. Bonnie Cummins finished out the year. Bonnie wore a fishing cap all the time. She also had false teeth, but she didn’t wear them all the time. Her brother was Howard Turner, another teacher."

Webb said the military gave him the opportunity to travel.

"I went to Fort Jackson for 16 weeks," he informed. "After the first week, I never saw anybody I knew. Nobody from DeKalb County. I was in the Army during ‘53 and ‘54. They sent me to Germany, and I went to Holland, Belgium, France, Spain, Italy, everywhere I could. I usually went by myself, and I learned the languages enough to get by. I went to England and saw the queen. She’s just five years older than I am. It was her birthday. She came out riding side saddle on a horse with Prince Phillip right behind her and she passed within a few feet of me."

After his release from the Army, he went back to the classroom.

"I got out of the army the last day of ‘54, and went back to college at Peabody with Uncle Sam paying for it," he said. "I got my Master’s Degree before the next school year started. I graduated on Friday, and the next week I started teaching at Rock Castle School. It was a one-teacher school, and I wanted to teach at a one-teacher school. There weren’t many left, and I wanted to have the experience. I taught over there for about two months, and they asked me to teach English at the high school. They thought I’d be tickled to death to go to the high school, but I would have been satisfied to stay there. I told them I would do whatever they wanted, so they moved me to the high school. That was the year they put the cow in the high school.

"It was Halloween, and you didn’t really do trick-or-treat back then. It was just trick. You took peoples’ porch swings off, and took their gates down, things like that. I had told Mr. Denton, the principal, that I had heard the kids talking about pulling something at the school, and that we might need a watchman. He wasn’t too worried about it, so I wasn’t either. Six of our young men, all football players, went to a nearby barn and took a cow out.

"They drove it up to the school, and they were going to put her upstairs in the auditorium, but she wouldn’t go up the steps, so they led her down the steps to the girls’ restroom. That’s where she was the next morning. I came in early, because I wanted to see what had been done. As I started up the walk, the office window opened, and a chicken flew out. Mr. Denton was throwing chickens out of his office. He was really mad. Then somebody came in and said there was a cow in the restroom, and a wagon in then old gym. That didn’t make him any happier. It was just a shambles.

"He thought I knew who did it, which I did, but I had already told him all I was going to tell him about it. He stayed mad at me for the next year. He gave me six classes the next year. I didn’t care.

"The next year I moved to the elementary school. I had a split class with 12 fourth-graders and 12 fifth-graders. I loved it. We had musical programs, and we had a good time."

His career as a librarian began soon after.

"The next year the state required the county to have a certified librarian at Liberty," Webb shared. "I was the only one in the school system, so I went down there for two years, the last two years of Liberty High School. I went to the new high school when it opened, and taught German, Spanish, history and English until Ms. Nell McBride retired, and I went to the library. I still taught a class of some sort the rest of my time with a school system."

Webb was inadvertently involved in the integration of schools in the county in his first year at the new school.

"I was at the high school when we integrated in 1963," Webb disclosed. "Liberty was already coming up here to the new school, and the high school there was closed. It was registration day, the first day of school, and the new high school had just opened.

"The black children were riding Trailways bus to Lebanon to go to school. Four of them came to register at the new school, and word got out to the sheriff. He got the former sheriff, and they came to the school.

"When I came in to the building I saw the kids sort of standing over by themselves, and my first thought was that this was something we hadn’t planned for," Webb said. "I thought I should go over and welcome them, so I did. I asked them if they had seen the school, and of course they hadn’t, and I hadn’t either, so we took a walk to have a look at the school.

"We got over to the Ag Building, and the two men came in. One of them said, ‘Get out of here, you can’t go to school here.’ I told the kids to go into the band room while I talked to these men. I told them it had been seven years since the decision was made; they had already had the trouble in Arkansas with the federal troops leading the students into the school, I said the best thing we can do is to not have any trouble, and just go ahead with it.

"They said ‘By God, we won’t have them in the school here, and we don’t need people that want them to be teaching out here either.’ I told them I really would like for us to do the best we can, and not have a big stir over it. They said ‘We’re going to leave, but we’re coming back, and we’re gonna run themout of here.’ So they left.

"I got the kids out of the band room and told them to go register like everybody else, and I went and told Mr. Snyder, the principal, exactly what had happened. They didn’t come back. I still thought something might happen. I slept in a front bedroom, just a few feet off the street, and I felt kind of exposed. That night I went to the back bedroom. In the night someone shot into Robert

Fisher’s house. He had let his children register at the elementary school.

"Public opinion kind of turned when that happened. White people weren’t eager to integrate, but they didn’t like them shooting up that house. In the end the kids registered, and they went to class, and schools were integrated in DeKalb County. It could have been a lot worse."

Webb found his wife, the former Audrey Turner, in the middle of his life.

"I married in 1976, he shared. "We had our 40-year anniversary last year. I had known the Turner family for a long time. They had a fine grandmother and granddaddy. If they’d all turn out that good they would have been great. William had 10 children, eight boys and two girls. Charlie lived next door, and he had six children, five of them boys. Ten years after the sixth, he saw Will getting ahead of him, and had four more. My wife Audrey was one of the second litter.

"I didn’t know her as well, but when Charlie died I went to the funeral home, and Audrey’s sister asked me how old I was. I told her 44. She said ‘You and Audrey ought to get together, she’s 37, and she’s not married yet either.’ I thought about that for a little bit, and they had killed hogs the day he died.

"They had all this sausage ground, and she was going to can it, so I volunteered to help. That was our romance. We went to a few movies, and we went to see one called ‘Porkies.’ We started to leave the theater, and she wanted to wait a little bit. I asked why we were waiting, and she said ‘I don’t want anybody to see me coming out of this theater. I don’t want anybody to know I had anything to do with this trashy mess.’"

While often referred to as the county historian well before then, he was officially named to the post in 1965. His personal files, including information concerning the history of DeKalb County, which he has been collecting for more than 70 years, were transferred to the Tennessee State Library and Archives in 2014. Copies of his collection were made for Justin Potter Library in Smithville, and remain in the genealogy room, which is named for Webb.

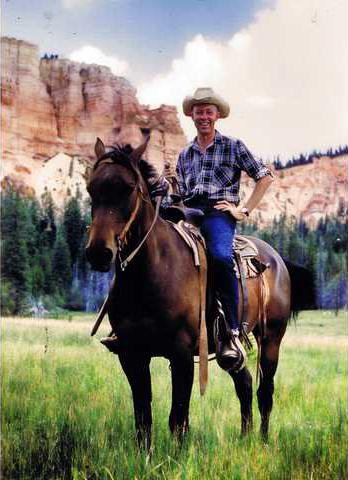

"In 1965 it became a requirement that every county have a historian. I was in Utah. Billy J. LeFevre, the county judge, had my mother write me a letter asking if I would accept the position. I was planning to come back here at the end of the school year anyway, so I accepted."

Webb has written five books, a history of the county and four family histories.

"I have done all these books and never made one dime from any of them. The money has all gone to the county libraries," he said.

"The thing I have learned about family history is that all the families are about alike. They all have some that are excellent people, people you can brag about being kin to, and the same families have some that are just awful, and you hope nobody knows you’re kin to them.

"Every family in DeKalb County, consistently, throughout the history of the county, is the same. We have no aristocracy here. Everybody has good and bad. I included some people in my books that were just as sorry as they could be. I put it all in, for better or worse. My great granddaddy had two children with a woman that was not his wife. I put them in too. I believe in truth."

Among Webb’s other pursuits are pottery, cemeteries, and picky eating.

"I have always been peculiar about my eating," he said. "I eat what I like, and I will not eat anything else. I do not like hot dogs and bologna. I will not eat either one. People thought I was crazy. When we’d have a weenie roast, I would eat a bun. I don’t drink Coca-Colas. I hate them. I drank one Coca-Cola in my life and it burned going down. Why would people pay for that? I don’t drink beer, and I don’t drink coffee or tea, either. Orange juice, tomato juice, water and milk. That’s it."

Webb also collects local pottery. "I have a churn in every corner," he said.

He has done extensive work recording old cemeteries as well.

"I’ve recorded nearly every cemetery in the county," Said Webb. "Bob Wall and Doris Gilbert went to some, and Audrey and I went to the rest. We have all the old ones documented."

And he performs marriage ceremonies.

"I’ve married 42 couples. I’m an ordained deacon, I attend Calvary Baptist, where a lot of my family goes," he shared.

Webb said that his best advice is to do your best.

"Do the best you can. Nothing’s going to be perfect, so try to do the best you can, and follow God’s plan for your life. You don’t always recognize God’s plan. It takes a while," he said.

Webb said his grave marker tells the story best. "My tombstone says ‘A Lifelong Democrat.’ It’s carved in stone," he concluded.